Hans-and-Lea-Grundig-Prize 2021

The 2021 Hans and Lea Grundig Prize has been awarded to artists Rajkamal Kahlon (Berlin), Rudolf Herz (Munich), and Natacha Nisic (Paris), as well as to art historian Dorothea Schöne (Berlin). After intensive discussion, the nine-member jury headed by Rosa von der Schulenburg and Eckhart Gillen made its majority decision on 19 May 2021 in Berlin.

The submissions from artists Carla Adra (Paris) and Jessica Ostrowicz from Birmingham, as well as the art historian Peter Chametzky (University of South Carolina, Columbia, USA), received honourable mentions.

The prize received more than 240 submissions, including works from the USA, Israel, Switzerland, the UK, Norway, and Ukraine, as well as artists from abroad living in Germany.

Rajkamal Kahlon was awarded in the visual art category for her anti-racist and anti-colonial work The People of the Earth. Rudolf Herz received the prize in the same category for his three-part project on the politics of remembrance entitled The Lenin Complex.

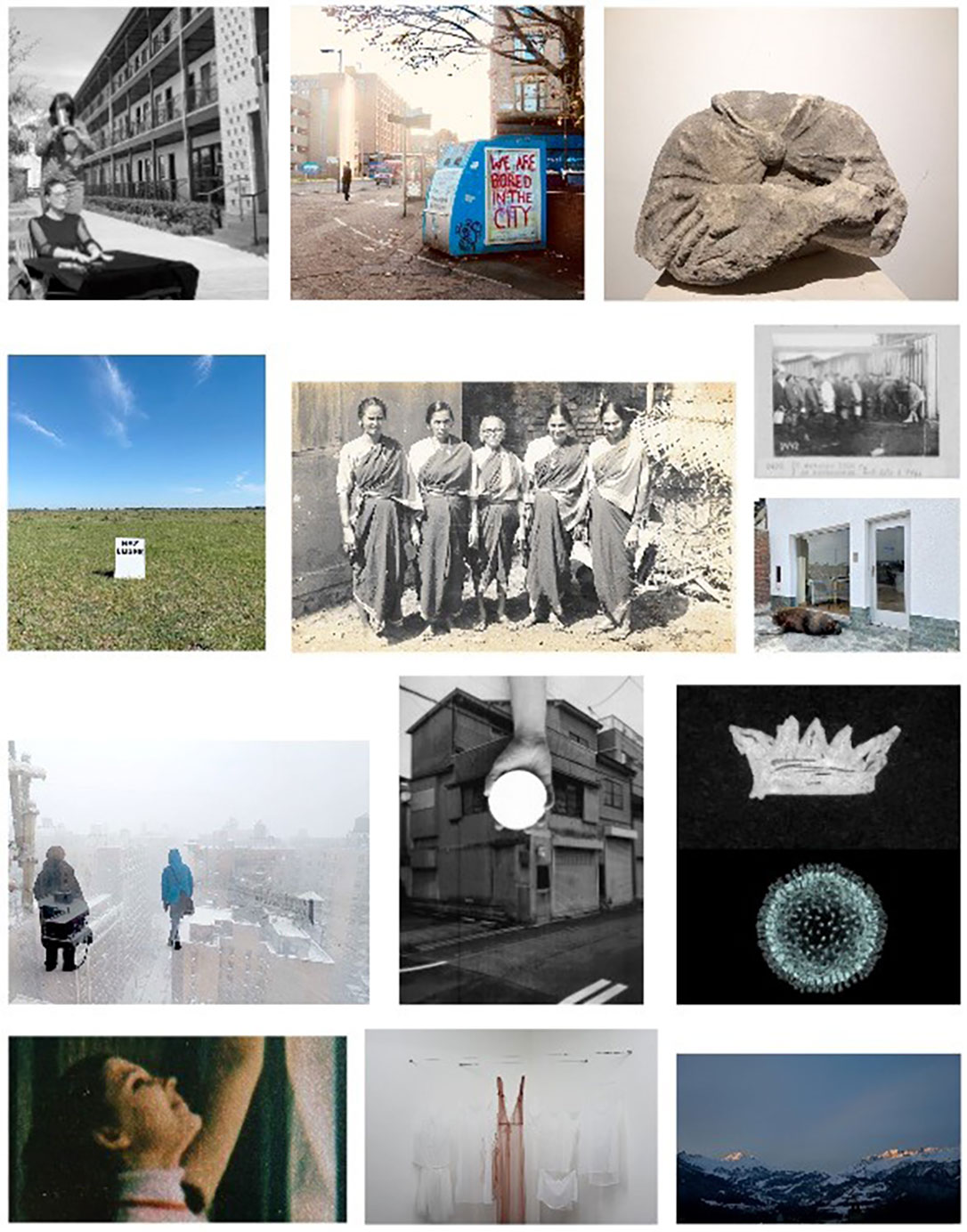

Natacha Nisic won the art education and outreach category with her collaborative online project The Crown Letter, which has presented and brought together artists from all over the world during the coronavirus pandemic. Dorothea Schöne won the art history category for her biographical exhibition project on the almost forgotten Berlin sculptor Joseph M. Abbo, who fled the Nazis in 1935 and died impoverished in exile in London.

The award ceremony was planned for 12 December 2021 (Sunday) at the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt am Main. Unfortunately, due to the pandemic, it cannot take place and has been postponed to next year. Information on the new date and venue will follow.

On the reorganisation and development of the prize since it was taken over by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung ten years ago, the publication „Kunst als Widerspruch. The Hans and Lea Grundig Prize 2011 – 2021“ [LINK] has been published.

Statements from the Jury of the Hans-and-Lea-Grundig-Prize 2021

Artistic Projects

Rajkamal Kahlon

Artist Rajkamal Kahlon received an award in the category of visual art for her work Die Völker der Erde (2017–2019). In this work, which was exhibited in the Galerie Wedding in Berlin, Khalon explores an ethnographic textbook from 1902. Lavishly illustrated with portrait photographs, the book aimed to present the customs and practices of all the peoples of the earth to the public. The artist considers every one of the publication’s approximately 300 pages, using drawing-based techniques to both alienate and approach the subjects depicted and to liberate them from the stereotypical gaze of the ethnographer and their photographer. By drawing and painting over the photographs, Kahlon brings those portrayed in the book into the present and at the same time places them in a critical relationship with the legacies of racism, colonization, and discrimination. Her interventions decode forms taken both by colonial discourse and the modernist canon. Not the least among the things that make the work unique are its allusions to the work of Hans and Lea Grundig, whose prints and painted works took up a critical relationship to war and oppression and called for the peaceful coexistence of all peoples and the protection of human rights. (Ines Weizman)

Rudolf Herz

The 2021 Hans and Lea Grundig Prize for visual arts goes to Rudolf Herz for his multi-part project LENIN KOMPLEX. It consists of three parts: LENINS LAGER: ENTWURF FÜR EINE SKULPTUR IN DRESDEN (1991), LENIN ON TOUR: EINE PERFORMANCE, EIN BUCH, EINE AUSSTELLUNG (2003 to 2009), and the film SZEEMANN AND LENIN CROSSING THE ALPS from 2019.

The project LENIN KOMPLEX (Lenin Complex) is characteristic of Herz’s conception of art, which is oriented towards the conceptual and pursues “strategies of aesthetic transformation on the basis of critique and research”. For Herz, an “engagement with questions of collective memory and the politics of images” plays a central role. “My art aims less at making appeals to the viewer by means of particular messages than at headstrong works that prompt reflection and invite dialogue. They transcend the boundaries between genres and point towards ruptures and changes of direction. My artistic work has sometimes been described as ‘artistic research’.”

The work LENINS LAGER: ENTWURF FÜR EINE SKULPTUR IN DRESDEN (Lenin’s Pallet (or Lenin’s Camp): Design for a Sculpture in Dresden) focuses on the Lenin monument, which at the time of the work’s conception was scheduled for demolition. The work also takes up the debate over the post-revolutionary political iconoclasm in the former East Germany after 1990. With his project, Herz takes aim at what he called a “cleansing action” that, in his words, aimed to “hide the denigrated monument from view, withdraw it from collective memory, and seek to remove a spur to controversy and discussion”. With the work, the artist also makes the city a counter-offer: to pull the memorial down, and yet preserve it on the very same site in demolished form, thereby putting the iconoclastic process on permanent display and saving the memorial from definitive erasure.

From 2003 to 2009, Herz borrowed the torsos of Lenin and two anonymous comrades from gravestone maker Josef Kurz, who had purchased the parts of the demolished Dresden memorial, and used them to realize his project LENIN ON TOUR. In a performative production, the now siteless monument journeyed through postcommunist Europe on a flatbed trailer, generating site-specific situations that linked the new, present era with the one recently concluded. Herz’s byline for the tour was, “I’m showing Lenin to my contemporaries, and the 21st century to Lenin. Who’s going to explain it to him?” Harald Szeemann invited Herz to exhibit the relics in Ticino in 2003. “During the trip, Szeemann talked to us about the possibility of Lenin having visited Monte Verità, and about the relationship between art, anarchism, and utopia.” The video recordings of the journey disappeared and were only rediscovered years later. In 2019, Herz used them to produce the film SZEEMANN AND LENIN CROSSING THE ALPS, one more grandiose presentation of alpine crossings through the political and aesthetic crags of the 20th century.

The jury acknowledges the high degree of theoretical reflection, the persistence, the situation- and site-specific curiosity, and the aesthetic brilliance of this long-term project by Rudolf Herz. The preject series LENIN KOMPLEX will remain specially connected with Dresden, the city of Hans and Lea Grundig, even if that be by continuing to point to missed opportunities for a more reflective farewell to communism, and by making up for them in art. (Thomas Flierl and Luise Schröder)

Communication of Art

Natacha Nisic

The prize in the category of outreach and education goes to French artist Natacha Nisic for the online project The Crown Letter. Art and culture were among the socio-political domains that suffered most during the COVID crisis: museums and galleries had to close, theatres shut down, film and book projects were postponed. Creative workers of all kinds were deprived of opportunities to present and exhibit their work and to be in contact with one another, their patrons and their audience—in short: their professional existence became precarious in the extreme.

Considering these effects of the pandemic, in soliciting submissions for this year’s Hans and Lea Grundig Prize the jury focused on curatorial projects that had taken shape during COVID and were striving to make art accessible under the new conditions imposed by the virus. Surprisingly, the response remained modest, with around 250 entrants. However, the portfolio of Paris artist and film-maker Natacha Nisic contained a remarkable approach—presented in a very understated way: the online project The Crown Letter. Created by Nisic during the first lockdown on 21 April 2020, to date the website crownproject.art presents the works of almost 50 international women artists, including video and photographic art, installations, and essayistic contributions. The works are made available worldwide once a week on Tuesdays. According to Nisic, the platform is a meeting-point for subjectivities. Personal statements are as much a part of the project as political ones—for example, works published during the week of 18 to 25 May 2021 focused on the exploitation of nature, feminist struggles, the conflict in the Middle East, and social utopias. In an interview, Nisic said that she wanted to create a “space for free artistic expression, visibility, femininine presence”. Beyond these things, The Crown Letter offers a space for networking, exchanges, and mutual support among the artists—an approach that impressed all the members of the jury. (Henning Heine)

Art Historical Works

Dorothea Schöne

The prize-winning entry by Dorothea Schöne is an exhibition project that she prepared as managing director of the Kunsthaus Dahlem in Berlin over several years and realized in 2020. Kunsthaus Dahlem is housed in a building that once served as the studio of Arno Breker, one of the most frequently employed sculptors in Nazi Germany. From 1937 onwards, Breker used the studio to create architectural sculptures for Albert Speer’s monumental buildings and to find sculptural expressions for Hitler’s propaganda. Since the building opened as an exhibition space in 2015, both women and men artists who suffered under the Nazi dictatorship have been commemorated. Among them is the wrongly forgotten sculptor Joseph M. Abbo. Abbo was born at the end of the 19th century (the exact year is unknown) in Safed in Palestine (present-day Israel), came to Berlin on a scholarship ca. 1911, and in 1913 began to study sculpture at the Königliche akademische Hochschule für bildende Künste. Renowned gallerists of the time—including Paul Cassirer, Alfred Flechtheim, Ferdinand Moeller, and Israel Ber Neumann—admired Abbo’s work, which was also purchased by Berlin’s Nationalgalerie. Jussuf Abbo was so integral to the Berlin art scene that Else Lasker-Schüler dedicated a poem to him. When the National Socialists took power, Jussuf Abbo was attacked both as a representative of modernism and as a Jew. During their Degenerate Art programme in 1937, his works were confiscated and largely destroyed. Although Abbo was able to flee to London in 1935, he was unable to continue the run of success he had enjoyed in Berlin and died poor and in serious ill-health in 1953, and has remained an obscure figure until now. Research carried out in France, Israel, the UK, and the USA has resulted in the first publication to provide a comprehensive treatment of Abbo’s life and work. This research, publication, and exhibition project has met with so much interest that German museums have been able to identify numerous works, some of which had been considered lost. Among them are the portrait of the Berlin art historian and museum director Max Friedländer, which is held by the Angermuseum Erfurt. Besides Schönes’s commitment to making the work of the wrongly forgotten sculptor Jussuf Abbo known, the jury also acknowledges her efforts to honour the memory of artists who were ostracized, persecuted and, to a large extent, murdered under the oppressive regime established by the Nazis, and whose fates are symbolized by Jussuf Abbo, not least of all on account of the life he lived in exile. (Kathleen Krenzlin and Rachel Stern)

Short biographies

Rajkamal Kahlon

Born in 1974 in Auburn, California; lives and works in Berlin; studied fine arts at the University of California, Davis and at the California College of Arts; first solo exhibition in 2004 in San Francisco; recent exhibitions include Rajkamal Kahlon: We’ve Come a Long Way to be Together (2020, Amsterdam) and Rajkamal Kahlon: Enter My Burning House (2021, Sacramento, USA); 2019 Villa Romana Prize, 2016 SWICH Artist in Residence, Weltmuseum Wien.

Website: https://www.rajkamalkahlon.com/

Rudolf Herz

Born in 1954 in Sonthofen, Germany; lives in Munich and Paris; studies in sculpture and art education at the Academy of Fine Arts Munich and in art history at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and the University of Hamburg, PhD in art history and visual communication at the University of Oldenburg; fellowship at the Villa Massimo in 1995, winner of the competition for the memorial for the murdered Jews of Europe (1997); numerous solo exhibitions and publicly exhibited works, including in Konstanz, Karlsruhe, and Frankfurt.

Natacha Nisic

Born in 1967 in Grenoble; lives in Malakoff, Paris; studies at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and as visiting student at the German Film and Television Academy Berlin; Villa Medici Prize, Rome, 2007–08, Rolff-Stiftung, Gladbach, 2021; professor at the Beaux-Arts du Mans, 2009–12; recent exhibitions include Catalogue de gestes, MNAM, Centre Pompidou, Paris and Osoresan, Galerie Anne de Villepoix, Paris.

Website: http://natachanisic.net/

Dorothea Schöne

Born in 1977 in Berlin, artistic director and director of the Kunsthaus Dahlem in Berlin since 2014; studies in art history, politics, sociology, and philosophy in Tübingen and Leipzig; Fulbright scholarship at the University of California, Riverside; assistant curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), 2006–09; PhD at the University of Hamburg in 2015 on Free Artists in a Free City: American Patronage of Postwar Art in Berlin; fellowships from the DAAD, the Getty Research Institute and the German Historical Institute; recent exhibitions include Der unbekannte politische Gefangene: Ein